Source Information: Wingate, U (2021). Reintroducing the process approach into EAP teaching. Proceedings of the 2021 BALEAP Biennial Conference exploring pedagogical approaches in EAP teaching, Glasgow, UK, 6th-10th April.[online].https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=f5LIWEQCSNI&list=PL0xk8t5VPtus2PcL-OBuiawe1Qls3lo-K&index=2

SF TEAP competencies being addressed

SP 10: You apply knowledge of specific academic contexts to materials or learning resource design

ST 8: Your teaching develops students ability to navigate conventions and values of current educational contexts

ST 1: You demonstrate a broad knowledge of EAP theories and academic contexts to inform EAP provision at institutional level

ST 10: you raise awareness of discourse features in writing

ST 11: You train your students to investigate the practices of a discipline

Summary of Source

In this presentation, Wingate documents her research into the research and writing practices of students at her institution, while highlighting the successes of students who adopt a process approach to writing to support their subject specific assessment tasks. Her presentation follows a typical structure for academic research dissemination, starting with a rationale for her study, a look at the literature surrounding the area, an explanation of her research methods and then a discussion of her findings. She also makes some interesting comments at the end that ground her work in the context of EAP practitioners’ teaching and promotion of academic literacies in HE institutions.

She makes a convincing argument for the need for EAP practitioners to include parts of the essay writing process in their work. Although not suggesting that this approach should come at the expense of a genre (product) based approach, (in fact she argues that both approaches can work in tandem), she makes the important point that the process approach may often be side-lined in EAP modules/courses and its facets are key to developing successful academic writers. Her research project analysed the approaches of 13 students when tasked with small-scale research and writing assessments in different disciplines. The analysis of her participants focused on these features of the writing process; time allocation to parts of the process; understanding functions of planning and reviewing; and source use, indicating that more successful student writers tended to adopt detailed application of strategies and approaches within these sub-parts of the process. At the end of her talk, she points to specific interventions that EAP tutors/course developers can adopt to support students, such as raising awareness of time allocations needed in each part of the writing process, while stressing the need to focus on source usage and its synthesis to the discipline specific demands of students’ written assignments. She also points to the importance this approach has in teaching academic literacies, while encouraging a collaborative approach to teaching, moving EAP interventions away from bolt-on, study-skill provisions.

Reaction to Source

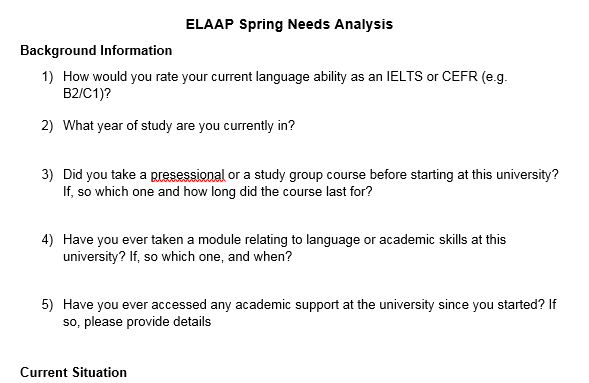

Wingate’s argument that emphasizes the teaching of EAP related modules and courses around a process approach is one that I agree with. In fact, for the last 5 years I have been teaching on and convening an study skills module (Academic Development) that adopts a process approach in its design and delivery. I have mentioned this EAP context in previous posts (‘Promoting equality of opportunity…’), but here is a brief summary of module for you, in case you need a reminder:

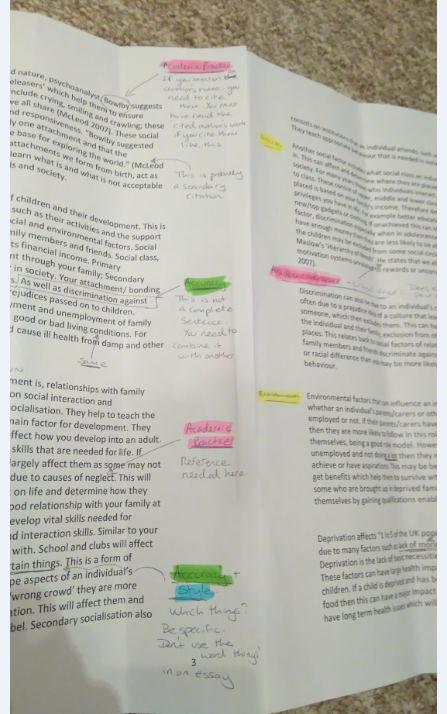

The Academic Development (AD) module is a core Foundation Year module, spread across two university terms. The cohort is comprised of mainly British students who had failed to make their A-level grades and are taking this course to progress onto a degree at UoS. The AD module teaches students academic skills akin to those found on a pre-sessional course, such as research and reading skills, writing composition skills and other skills relating to academic practice and conventions of their incoming academic departments. The module guides students through similar stages in Wingate’s process model through the deconstruction of essay questions, collection, and evaluation of source material, planning of argument and reviewing of composition.

Teaching this process approach to students has been useful and important in highlighting differences in writing approaches. Many of the students I have taught over the years describe school experiences of writing as a product-driven endeavor, with very few having experience of, or realising the importance and effort required to carry out relevant research to inform the writing of academic genres at HE level. However, teaching the process approach is not without its complication, and I have found that students still need specific scaffolded support in the form of memorable frameworks to help them approach the skills of finding, evaluating and connecting source material to the arguments they intend to make in their essays. In the next section I will outline such a framework that I devised, inspired by Legitimation Code Theory’s semantic gravity dimension.

Application to my practice

To support my students, and other AD tutors’ investigation into writing practices of the subject areas of their students, I developed a conceptual framework relating to different levels of research needed in essay writing. This ‘Pyramid Approach to Research’ (PAR) is informed by Legitimation Code Theory’s Semantic Gravity (Maton, 2013), and supports gathering of supporting source material for essays’ arguments, representing different knowledge types. The aim of this framework is to ensure that the written arguments students will eventually compose demonstrate discourse patterns that move between context independent and context dependent concepts, a key feature of critical and analytical writing (Maton, 2012, cited in Szenes et al, 2015).

The PAR is analogous, utilising a diagram of a pyramid with three constituent parts, coupled with a notion of structural integrity that links to argument strength. The bottom or base of the pyramid represents a ‘point’ the students want to make in a part of the essay; the central part of the pyramid is called ‘broad based support’ and the top level is called ‘empirical example of case-study’. If students can support a ‘point’ in their essays with information at these levels, their argument will have strength and structural integrity. Relating this to LCT’s semantic gravity, the point (or pyramid) being written in the essay would ‘wave’ from CI (SG-) to CD (SG+) knowledge. If the students find just the top level of support (empirical examples or case-studies) for their point, they are shown that the pyramid would ‘collapse’ as the middle part (broad based support) is absent. Similarly, they are shown that if they find the ‘broad based support’ for their point, then their pyramid will remain intact but is incomplete. The same analogy can be applied to the argument that they are making in their written work, being linked to the idea of Semantic Flat Lining (Maton, 2020).

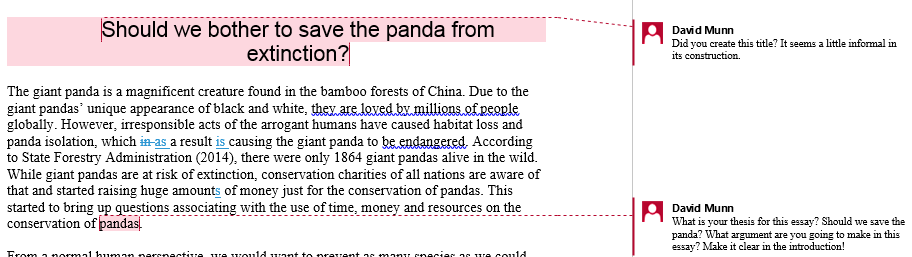

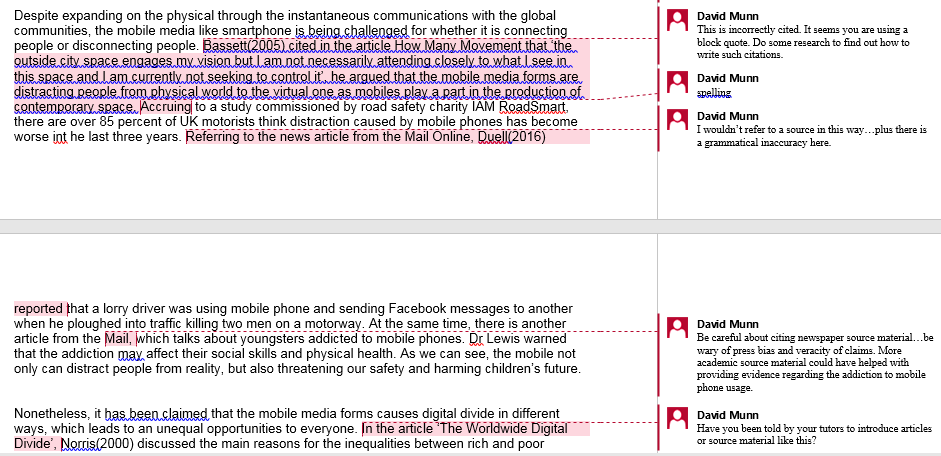

I have utilised this approach in my own teaching with students in the Business strand of the AD module. I used a business essay question along with two texts and accompanying guiding exercises to help students identify how source material in this discipline could be used at different levels of the pyramid to support an argument (see extract below). Using these materials led to interesting discussions with students about the types of source material that could be used to support the top level of the pyramid, such as whether media related sources would suffice. Some of my Business students attested to the importance it gives them in structuring and planning their research in an academic subject area they are transitioning into.

The idea is that once the student has gathered the source information above and linked it to the ‘point’ they intend to make about digital and social media marketing (in the case above), they would write this out in a paragraph (or two), starting with the ‘point’, then including a summary and connection to the ‘broad based support’, and then finally they would include detail about the ‘example/case study’ in their prose, while linking this to the ‘point’. Analysing such a text across one or two paragraphs would result in a semantic wave profile that moves gradually from CI to more CD forms of knowledge, in line with what LCT would describe as being more analytical and critical writing (Martin, Maton and Doran, 2020).

The PAR is equally useful for AD tutors to help investigate the disciplinary differences to academic practice of the students they are working with on the AD module. For instance, tutors can use the framework to guide their questions to liaison subject tutors about the types of support that are needed in the pyramid; whether the pyramid can relate to discourse produced in that discipline; and what types of source material would be best to consult at the different levels of the pyramid. The following example show how another AD tutor used this approach to support her students studying Arts and Humanities prepare for a presentation assessment.

Your Reaction

- Do you think that my PAR approach is a suitable way of teaching ‘literacies’ (as Wingate mentions) to students? Can you see any potential limitations or problems with this approach?

- Do you have any novel ways of supporting students through teaching the process approach to writing? Why are they successful and how to you scaffold them?

References

Martin, J. R., Maton, K., & Doran, Y. (2020). Academic discourse: An interdisciplinary dialogue. In J.R Martin, K. Maton, & Y. Doran, (Eds.), Accessing academic discourse systemic functional linguistics and legitimation code theory (pp. 1-31). London, England: Routledge

Maton, K. (2013). Making semantic waves: A key to cumulative knowledge building. Journal of Linguistics and Education, 24(1), 8-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2012.11.005